This article is based around notes made during the Pelvic Floor Health Café we hosted with Helen Hodder, a physiotherapist specialising in pelvic floor function.

What are the pelvic floor muscles?

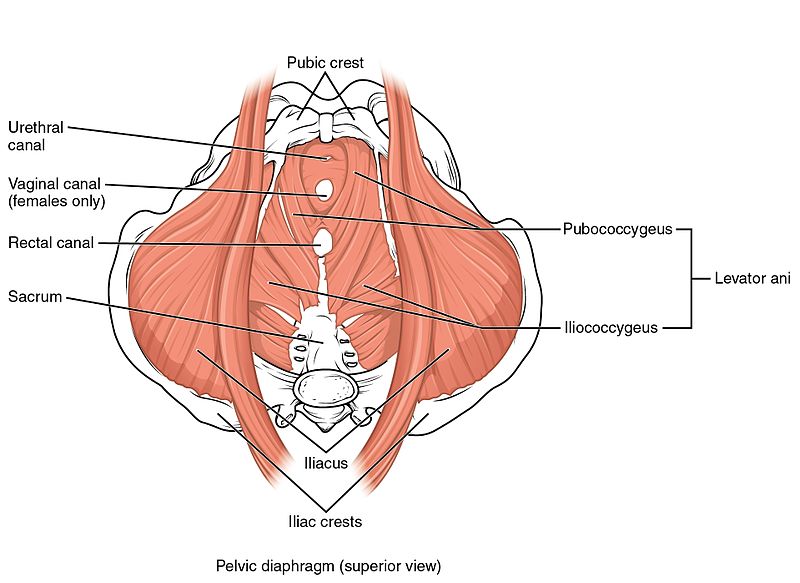

The pelvic floor muscles form a sort of “trampoline” at the base of your pelvis, stretching between your tailbone (at the back), pubic bone (at the front), and sit bones (the sides):

What do they do?

It’s important to think of the pelvic floor muscles as being multifunctional. They don’t just hold everything in. As with any other muscle, it is just as important that they are able to relax as contract.

They:

- Control the pelvic openings (anus, vagina, urethra) and help prevent incontinence

- Support all the pelvic organs (bladder, uterus, vagina, prostate, small and large intestine) and help to prevent prolapse

- Help with sexual arousal and sexual function

- Help stabilise the joints in your pelvis

Pelvic floor dysfunction can affect people of all genders and stages of life, though pregnancy and birth present particularly gnarly challenges to the pelvic floor.

How to contract your pelvic floor muscles

There are some positions that are particularly effective for “feeling” these muscles:

- Sat down, leaning forward with your elbows on your knees

- In Balasana (Child Pose), with your knees wide

- In Ananda Balasana (Happy Baby)

- In Mandukasana (Frog Post)

In any of these poses, breathe out and imagine you are trying to stop yourself from peeing or breaking wind – tighten and close the muscles around your anus, then your vagina / prostate, and lift up your internal muscles. Helen gave a visual cue of “picking up a handkerchief”, or you can imagine the way a jellyfish swims.

If you can’t really feel it, try it sat down with a rolled up towel placed under your pelvic floor – that should allow you to feel the difference as you contract.

Once you are confident with this, try it standing up. This will feel harder since gravity is providing extra resistance.

How to relax your pelvic floor muscles

There are some occasions when it is very important to be able to fully relax the pelvic floor, and holding permanent tension can cause problems in the same way not being to contract can.

Pelvic floor relaxation is passive – it should feel like an expansion and relaxed stretching of the muscles, not an active “pushing down”.

SMR for the pelvic floor

If you are still struggling to feel the difference between contraction and relaxation of your pelvic floor, you could try doing some self-massage (“self myofascial release”) to prepare:

- Take a firm ball about the size of a tennis ball and sit on it, placing it between your anus and urethra

- Apply some pressure from the ball onto the pelvic floor and see if that helps release tension

- You can try some strong contractions while doing this too – tense against the ball for 5 seconds and then breathe out and try to relax the muscles you were tensing

- Spend at least 2 minutes doing this and then have a rest before trying the exercises again

The connected breath

Increased stress can cause chronic tension in the pelvic floor muscles (and other muscles). This may be a reason why your pelvic floor feels unresponsive. Helen said that she had noticed a shift in the women she works with and is now prescribing relaxation exercises far more often than she prescribes contractions.

There is a strong connection between breath and stress – when we are stressed, the hypothalamus in our brain activates our sympathetic nervous system (“fight or flight” response), we become adrenalised and start to breathe more quickly and shallowly, our heart beats faster, more blood floods the muscles… This can be very useful in short bursts in truly dangerous situations, but a lot of the time nowadays that perceived danger is in response to long-term work demands that don’t benefit from a stress response…

Thankfully, we can use deep breathing to activate our parasympathetic nervous system (“rest and digest” response) and help our body to relax:

- Begin by lying on your back with your knees raised

- Place one hand on your tummy and one on your chest

- As you breathe in through your nose, try to feel the lower hand raise while the hand on your chest stays still

- Imagine you are inflating a balloon in your torso, allowing it to expand up to the ceiling, out towards your lower ribs and lower back, and, of course, to your pelvic floor muscles too – allow them to relax

- As you breathe out through your mouth, allow all of those expanding muscles to contract, deflating that balloon and creating slight tension (say, 30%) in your pelvic floor and torso to help push that breath out slightly

- Work towards breathing out for twice as long as you breathe in for, with small pauses between the in-breath and out-breath

- When you can do this lying down, try it sitting up, and then standing

There are many breathing timer apps that can be very useful for this. Helen recommended trying to do this for at least 5 minutes every day, preferably three times a day – you can’t really do too much of it, and it feels amazing!

Training the pelvic floor muscles

Putting this all together, we could end up with a routine like this:

- 2-5 minutes of connected breathing

- 10 pelvic circles in each direction

- 10-30 short (1-2 second) contractions, being sure to fully relax between each one

- 10-30 longer (10 second) contractions

Once you can comfortably do 30 short contractions and 30 long contractions, you’ll hopefully be ready for using your pelvic floor muscles in more demanding situations – coughing, sneezing, laughing, sneezing, shouting, lifting, pushing, pulling…

The Knack

The pelvic floor muscles form the base of the musculature commonly referred to as your “core”. We can imagine this as a sort of cylinder with your pelvic floor at the bottom, your TVA (a sheet of muscle running from one side of your lower back, under your abs, to the other side of your lower back) as the walls, and your diaphragm (the muscle that draws air down into your lungs) as the top.

The activities listed above involve our core muscles contracting, and this causes an increase in pressure in our abdomen. The pelvic floor has to work harder to keep this pressure in. If we have some pelvic floor dysfunction, these activities can cause incontinence. To prevent this, we must use “the knack”.

In normal circumstances, this is an automatic reflex, but in some cases it may be necessary to train it.

- Cough strongly and see if you feel your pelvic floor muscles contract

- If not, try doing one of the short contractions you have practiced just before you cough

- Repeat this as often as you can until it becomes automatic

- An approach that is sometimes recommended is to do three short contractions after every time you notice any sort of leak or other dysfunction

Applying this to strength training

When training with submaximal loads, you should be able to breathe as you exercise. A good general rule is to breathe in during the easiest part of the lift and to breathe out on the hardest part. For example, if squatting, breathe in as you descend and out as you stand up. As you have practiced in your pelvic floor training routine, contract your core and pelvic floor muscles as you exhale.

If the load is light, this contraction need not be excessively strong. As the load increases, so will the strength of contraction.

If you can do this comfortably and with no pelvic floor dysfunction, you may be able to increase the load further, to a point where it becomes safer to use a different breathing technique – the Valsalva Maneuver

The Valsalva Maneuver

First, a disclaimer – do not use this approach if you have high blood pressure or know that you are at high risk of cardiovascular disease. It causes a spike and then drop in blood pressure that may be problematic. Instead, keep the loads slightly lighter and breathe as described above.

Otherwise, try this:

- Breathe in and hold your breath

- Strongly contract your core musculature to generate pressure inside your abdomen

- Do a rep of whatever exercise you’re doing

- Release the breath and reset after each rep (some people do two or more reps with one breath, but that can feel pretty gnarly)

If that all feels good and you’re really getting into this whole weightlifting thing, you may even consider using a weightlifting belt. This wraps around your torso to give your abdominal musculature something to brace against. At the end of his really extensive review of the available literature on belt use, Greg Nuckols concludes:

Get a good belt and use it, as long you don’t have any conditions exacerbated by higher-than-normal spikes in intra-abdominal pressure and blood pressure, or are a weightlifter for whom a belt doesn’t allow you to catch a lift as deep. As long as you don’t fall into one of those two groups, you’ll probably benefit from training with a belt most of the time.

In conclusion

It is essential to establish healthy pelvic floor function at every level of resistance. A system of standards might go something like this:

- Learn to feel your pelvic floor – use SMR and sitting on a towel if that helps

- Practice until you can do 5 minutes of comfortable connected breathing, slightly contracting on every exhale and fully relaxing on every inhale

- Work up to being able to do 30 short (1-2 second), strong contractions and 30 longer (10 second) contractions

- Develop the knack as you cough, and during any other sudden movements

- Try strength training with low weights, exhaling and contracting during the hardest part of the movement

- If you can do this without dysfunction, try the Valsalva Maneuver with no weight. You wish to start using this as you get stronger and lift heavier.

Establish comfortable proficiency at each stage before moving onto the next. Your control of your pelvic floor muscles should improve in the same way as any other muscle adapts to training. If things don’t seem to be changing, go and see a pelvic floor physio! They’re amazing and this stuff is really important.